Description of the Cave

People have always been infatuated by caves. Caves were shelters not only for our predecessors but also innumerable animals. They resemble otherworldly buildings created without human hands and some remain hidden from us. Behold the most beautiful dripstone cave in Poland.

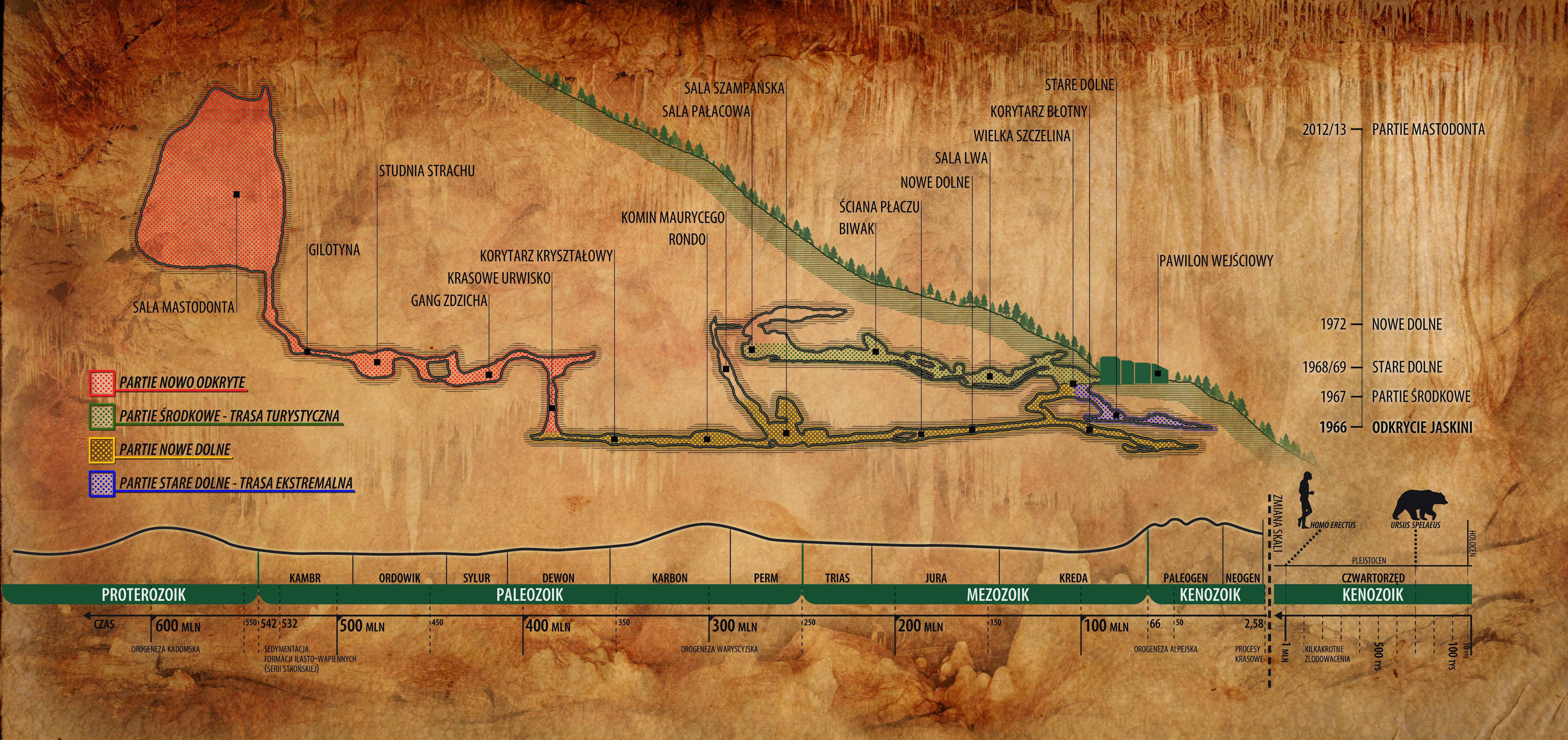

Layout diagram - levels of the cave inside Mount Stroma.

The Location of the Cave

The Bear Cave in Kletno is the longest cave in the Sudety Mts. and one of the longest and deepest caves in Poland. It is located in the Eastern Sudety Mts., within the Mt. Śnieżnik Massif, inside Mt. Stroma (1166 m a.s.l.).

Characteristics of Our Cave

The cave developed horizontally on several levels. The total known length of its halls and corridors is nearly 5 km, while its depth is more than 100 m. The upper level is only rudimentarily preserved. The middle level is open for tourism and offers a tourist route leading amongst one-of-a-kind and well-preserved speleothems as well as hosting a wide range of bones of Pleistocene animals.

Formation of Caves and Karst Phenomena

The formation of the Bear Cave is wholly related to the occurrence of carbonate rocks. In the case of the Bear Cave, these are marbles, i.e. limestone crystalline rocks of Precambrian age (about 600 million years old). The marbles make up part of the geological structure of the Mt. Śnieżnik Massif. Due to the effects of water erosion, karst phenomena have developed in these marbles and formed this beautiful example of a karst cave, the Bear Cave.

Dripping Water Hollows Out Stone...

The stream called Kleśnica churns at the foot of the Bear Cave. The waters of Kleśnica, to a large extent, carved the Bear Cave. This process started about 28 million years ago, when surface waters initiated the creation of an underground cave system. Both Kleśnica and the surface waters joined forces and flowed through a system of cracks and fissures existing in the rocks, forming corridors, halls, and chimneys over millions of years. This water not only destroyed the rock mass but also gave rise to a great variety of miscellaneous speleothems of many forms and colors.

Not Oly Bears...

During times of glaciation, sediments that were rich in the remains of animals living at that time were formed inside the Bear Cave. Most of the animal remains belong to one cave bear (Ursus Spelaelus), thus we have the name of the cave. However, the bones of a cave lion, cave hyena, wolf, bison, marten, bats (several species), beaver, roe deer, wild boar, fox, and many rodents have also been found here. The origin of these remains varies. These are the bones of animals both inhabiting the cave, and who were victims of predators, and eventually the bones were deposited in the cave by water.

Speleothems of the Bear Cave

Among the other caves in Poland, the Bear Cave is distinguished by diverse, opulent, and well-preserved speleothems.

These are made of calcium carbonate, which accumulated in water deposits in the cave in a crystalline form, i.e. calcite. Calcite has cemented underground collapses and covered the walls of the cave with calcite dripstones. Over time, the cave has become decorated with a wide variety of different shapes and sizes of calcite forms.

The most characteristic forms are described below.

The speleothems of the Bear Cave not only consist of stalactites and stalagmites but also exceptionally rich cave floor formations. These include rimstone dams filled with water, calcite brushes, and calcite flowers crystallizing on the surface of rimstone dams, forming structures similar to coral reefs or rice paddies, and finally, cave popcorn resembling cauliflowers. At the bottom of the cave, cave pearls (or pizoids) can be seen. The water in the cave continuously builds the speleothems, although these changes are imperceptible to the human eye.

The increase in the amount of calcite build-up is estimated at approx. 1 mm3 per 10 years. The only evidence for of all these processes is the calcite-flooded bat skeleton, which becomes less and less visible every year under the layers of calcite. This is what makes us different.

The Speleothems of the Bear Cave

Makarony

Zwane też rurkami naciekowymi. Z kropli zwisających ze skały wytrąca się osad węglanu wapnia, który wraz z upływem czasu nabiera kształtu cienkich rurek. Woda sącząca się wewnątrz wąskim kanalikiem powoduje wzdłużne narastanie nacieku.

Stalaktyty

Grawitacyjny naciek jaskiniowy mający zazwyczaj kształt wydłużonego odwróconego stożka (sopla), narastającego od stropu jaskini krasowej ku jej spągowi. Podobnie jak makarony, stalaktyty posiadają w środku kanalik którym spływa woda zwany kanalikiem alimentacyjnym.

Stalagmity

Przysadzisty naciek jaskiniowy, osiągający często duże rozmiary. Może występować w postaci stożka, słupa, guza itp. Narasta od dna jaskini krasowej ku górze wskutek wytrącania się węglanu wapnia z wody kapiącej ze stropu jaskini lub innego nacieku.

Stalagnaty

Naciek jaskiniowy w formie kolumny, słupa, łączący strop jaskini krasowej z jej spągiem. Powstaje on w efekcie równoczesnego rozwoju stalaktytu od stropu i stalagmitu od dna jaskini. Przy odpowiednio długim czasie przyrostu obu form leżących na jednej osi dochodzi do ich połączenia i powstania stalagnatu i z czasem kolumny naciekowej.

Nacieki grzybkowe

Drobne formy nacieków agrawitacyjnych, których kierunek wzrostu jest zawsze prostopadły do podłoża, bez względu na jego nachylenie. Ich długość rzadko przekracza 20 mm. Powstają z kalcytu wytrącającego się z wody, która podsiąka kapilarnie przez drobne szczelinki podłoża, lub z rozpryskujących się kropli.

Heliktyty

Nieregularne, ekscentryczne formy naciekowe powstające często w wyniku zwężenia lub zaczopowania kanalika zasilającego naciek. Te krystaliczne, zazwyczaj nieregularne, krzaczaste wyrostki rosnące w dowolnych kierunkach powstają zwykle na ścianach i stropach, a także na stalaktytach i polewach.

Polewy

Formy naciekowe w postaci grubych pokryw kalcytowych na ścianach i dnie, zbudowane z drobnokrystalicznego węglanu wapnia. W zależności od domieszek mogą przyjmować różne barwy.

Żebra i nacieki kaskadowe

Różnorodne formy zdobiące ściany oraz nachylony strop jaskini. Mogą zajmować duże powierzchnie, są charakterystycznie użebrowane w zależności od struktury skały, na której powierzchni powstają.

Nacieki wełniste

Powstają z mleka wapiennego, czyli uwodnionego węglanu wapnia o postaci gęstej wodnej zawiesiny mikrokrystalicznego osadu z różnymi domieszkami. Tworzą się na ścianie i stropie jaskini, często w kominach jaskiniowych. Swoją fakturą przypominają wełnę.

Draperie i zasłony

Ich powstawanie warunkuje powolny spływ kropli wody po ścianie lub stropie o odpowiednim nachyleniu. Mają ciekawe kształty przypominające zasłony lub tkaniny. Przenika przez nie światło jak przez materiał.

Pola ryżowe

Formy naciekowe powstające na dnie jaskini. Mogą być płaskie lub ułożone kaskadowo. Ich nazwa związana jest z podobieństwem do pól ryżowych widzianych z góry.

Misy martwicowe

Forma naciekowa, tworząca się na dnie jaskini ze skrystalizowanego węglanu wapnia i ma kształt niecki bądź misy. Jest efektem długiego cyklu odparowywania i wypełniania się niewielkich jeziorek jaskiniowych i wytrącania kalcytu na ich dnie i obrzeżach.

Pizoidy – perły jaskiniowe

formy kuliste, które powstają w wyniku koncentrycznego wytrącania się kalcytu wokół ośrodka krystalizacji, którym może być ziarno piasku lub okruch skalny, na dnie stojących lub wolno płynących wód jaskini.

Krystaliczne skupienia kalcytu

Skupienia ładnie wykształconych, często przejrzystych kryształów węglanu wapnia, tworzących na ścianach jaskiń zgrupowania w kształcie szczotek. Powstają także w głębi lub na obrzeżach jeziorek jaskiniowych, w warunkach powolnej i swobodnej krystalizacji.

Kwiaty kalcytowe

Krystaliczne formy kalcytu powstające w misach martwicowych i jeziorkach. Kalcyt krystalizujący na powierzchni wody przybiera płaski kształt przypominający pływające liście nenufarów.